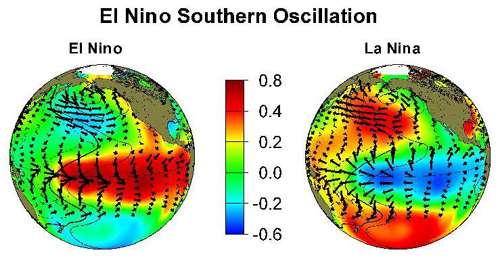

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and El Niño Southern Oscillation

(ENSO) influence sea surface temperatures, sea level pressure, and surface

winds in very similar ways. The most obvious difference between the

PDO and ENSO is the time scale. Whereas ENSO events tend to persist

on the order of one year, the PDO signature can last up to 30 years

(Mantua, 2001).

Additionally, while the PDO primarily affects the North Pacific region,

its effects can be felt near the equator. Conversely, ENSO primarily affects

the climate of lower latitudes, but its secondary effects are felt in

the North Pacific (Mantua, 2001). A positive, or

warm

phase PDO, produces climate and circulation patterns that are very

similar to El Niño. Likewise, a negative, or

cool

phase PDO, produces climate and circulation patterns similar to La

Niña (Gershunov and Barnett, 1998). This is documented in the following

two figures, which show how sea surface temperatures and surface winds

are influenced by (1) the positive and negative phases of the PDO and

(2) El Niño and La Niña phases of ENSO. Dark red and dark

blue indicate temperature anomalies of +0.8 C and -0.6 C, respectively.

Wind stress directions and magnitudes are indicated by vectors.

Source:

Mantua,

2000

Numerous studies have attempted to determine the effect

of the PDO and ENSO on each other. The results have been largely inconclusive

and/or contradictory. However, a study by Gershunov and Barnett (1998)

shows that the PDO has a modulating effect on the climate patterns resulting

from ENSO. The climate signal of El Niño is likely to be stronger

when the PDO is highly positive; conversely the climate signal of La

Niña will be stronger when the PDO is highly negative. This does

not mean that the PDO physically controls ENSO, but rather that the

resulting climate patterns interact with each other.