The

purpose of our wild horse study was to see if there were hoof wear

patterns that were consistent, unlike many domestic horses that have a

wide range of hoof shapes and wear patterns. Arrangements were made

with the BLM to examine wild horse feet once these horses were in

lateral recumbency. We found each foot packed with dirt in the caudal

region of the foot, around the frog and bars. The distance from the

frog apex to the wall at the toe was always shorter than what we

commonly see with domestic feet that are shod. It is common for

domestic hooves to have a wide range of distances from the frog apex to

the edge of the wall at the toe. The frog of domestic horses often

becomes distorted and stretched forward as well. The bars on wild horse

feet all terminated about ¾” caudal to the frog apex. The heels

were worn back to the frog buttress in one group of horses that lived

in a shale, granite and sandstone environment. Others who lived in

softer, less abrasive terrain had longer heels that would press into

the sand instead of being worn away, very much like domestic horses in

similar environments. All horses had a small enlargement of frog at the

buttress and apex that was calloused, showing signs of weight bearing,

again very much like what we see on domestic horses.

|

|

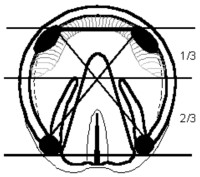

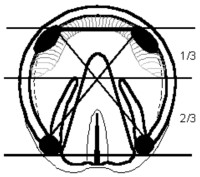

The

weight bearing part of the hoof is not limited to the hoof wall, but

rather includes portions of the hoof wall, the sole, and the frog, sole

callus, and the bars.

The

weight bearing part of the hoof is not limited to the hoof wall, but

rather includes portions of the hoof wall, the sole, and the frog, sole

callus, and the bars. The

hoof lands heel-first when the horse moves.

The

hoof lands heel-first when the horse moves. The breakover point occurs near the frog

apex.

The breakover point occurs near the frog

apex.