Artists conception of Precambrian period ( http://www.dc.peachnet.edu /~pgore/myphotos/rocks/precamb.gif)

Just Random Process?

A well accepted theory in the scientific community today is a theory of evolution and natural selection, based largely on the discoveries of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), a British naturalist. Darwin served as a naturalist aboard the H.M.S. Beagle on a science expedition around the world. Darwin found some fossils of extinct animals that were similar to modern species. On the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean he noticed many variations among plants and animals similar to those in South America. He traveled the world on the expedition, collecting specimens for study. When he returned to London, Darwin examined his notes and specimens, and proposed several theories, including that evolution did occur, that evolutionary change was gradual, taking millions of years, that the primary mechanism for evolution was a process called natural selection; and that the millions of species alive today arose from a single original life form through a branching process called specialization. His theory holds that variation within a species occurs randomly and that the survival or extinction of each organism is determined by that organism's ability to adapt to its environment to adapt to its environment. He set this theory forth in his book "On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection".

Although this theory can not be viewed on a large scale (macroevolution), it has been very influential in the scientific community. It is, however, highly criticized, and has yet to be backed by an immense collection of transitional fossils that the theory must include. It is hotly debated in the scientific community, and has been since Darwin proposed the theory, although he never intended it to. It also does not address probably the most important question: Where did life originate in the first place?

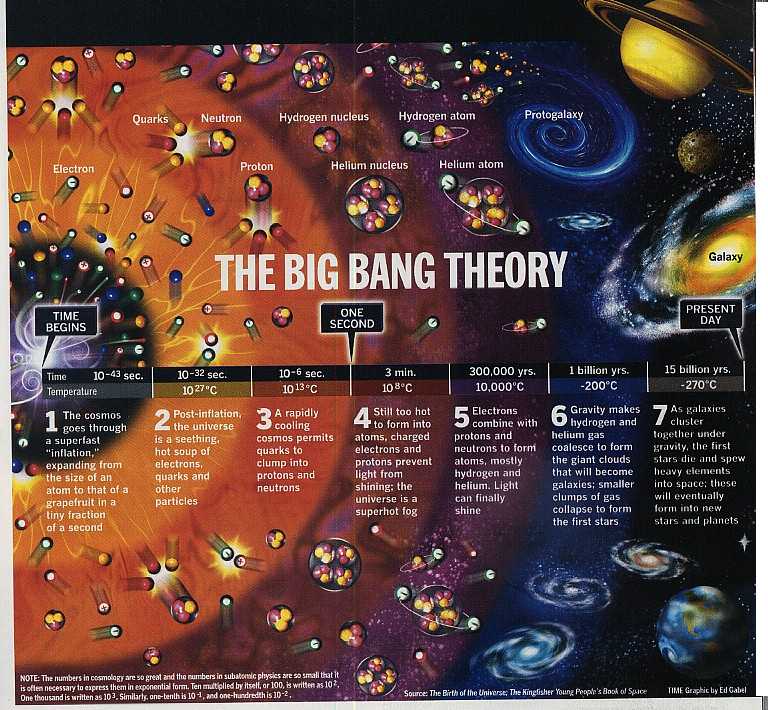

The common belief in the scientific community is a view presented by Soviet scientist Alexander Oparin in 1924 and British chemist J.B.S. Haldane in 1928. Their theory says that the earth's early atmosphere consisted of methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and water vapor with ultraviolet light acting upon this atmosphere, all coming from volcanic eruptions on the early earth. The theory says that these elements washed down by rain and accumulated in the primitive oceans until they reached a state of a hot dilute soup. Life supposedly emerged out of this prebiotic soup, by abiogenesis, or accidental processes. It seems unlikely that all that we see around us is the result of a random processes, but it became widely accepted, by many scientists such as Nobel laureate Jaques Monod, who wrote:

"Chance alone is the source of every innovation, of all creation in the biosphere. Pure chance, absolutely free but blind, is at the very root of the stupendous edifice of evolution. The central concept of biology...is today the sole conceivable hypothesis, the only one compatible with observed and tested fact. All forms of life are the product of chance..." - Chance and Necessity

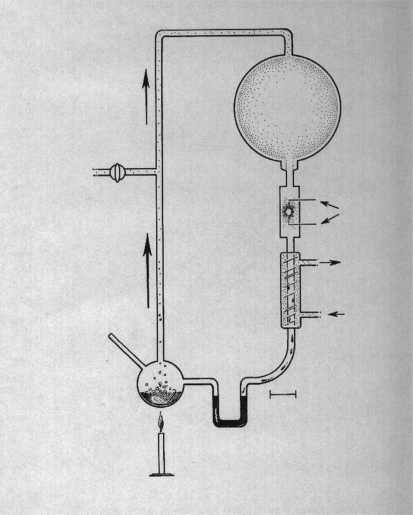

An interesting experiment was conducted to support this theory in 1950's when Stanley Miller and Harold Urey simulated this situation in a lab. In it, a similar situation as shown above. Using a high-energy spark, and with some time, a small mass of black tar was formed which contained amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein. Because of experiments like this, random abiogenesis came to be accepted as a sound theory.

However, despite these experiments and Monod's confidence, this theory has many problems. The most recent data indicates that there was most likely much more oxygen in the atmosphere at that time, which would prevent the amino acids from being formed. There is also no geological indication of this prebiotic soup, as microbiologist puts it: "Considering the way the prebiotic soup is referred to in so many discussions of the origin of life as an already established reality, it comes as something of a shock to realize that there is absolutely no positive evidence for its existence."

The probability of life emerging from random abiogenesis is also remarkably improbable, as Hubert Yockey in Information Theory and Molecular Biology states: "In so far as chance plays a central role, the probability that even a very short protein, not withstanding a genome, could emerge from a primeval soup, if it ever existed, even with the help of a deus ex machina for 10^9 years is so small that the faith of Job is required to believe it." Some supporters of the abiogenesis theory say that time provides the time for this process to occur, but this assertion was only valid before Einstein's equation's of relativity disproved his own belief and many others of a Steady State universe. So what exactly is the probability of abiogenesis occurring? Sir Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe calculated the chance to be very small:

"No matter how large the environment one considers, life cannot have had a random beginning...there are about two thousand enzymes, and the chance of of obtaining them all in a random trial is only one part in (10^20)^40,000 = 10^40,000, and outrageously small probability that could not be faced even if the whole universe consisted of organic soup. If one is not prejudiced either by social beliefs of by a scientific training into the conviction that life originated on the Earth, this simple calculation wipes the idea entirely out of court..." - Hoyle

Wickramasinghe added: "The chances that life just occurred are about as unlikely as a typhoon blowing through a junkyard and constructing a Boeing 747."

So from this evidence it is very speculative, if not absurd, to believe that we are here by chance and abiogenesis. But if the answer is not to be found in a prebiotic soup, what is the explanation for the emergence of life and ourselves? On the next two pages we will investigate two more interesting theories.