Edge Jumps

What is an edge jump? How are they different from toe jumps?

An edge jump requires the skater to skate on an edge (that is, one side of the blade, rather than the toepick or entire bottom of the blade) right up to the moment the skate leaves the ice; the toepick has only an incidental role in edge jumps.

There are many edge jumps that figure skaters learn, but the three most commonly known are the Salchow, Loop, and Axel. These jumps are the most popular because they are more easily made into double, triple, and quadruple variations.

I thought the toepick is what lets a skater put pressure on the ice? Where does the "power" come from in an edge jump?

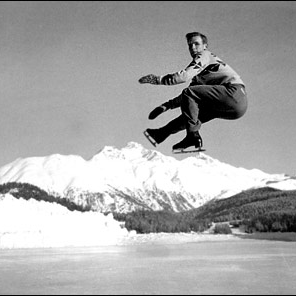

Interestingly, many of the same takeoff techniques still apply to edge jumps, but the skater goes about achieving them in a different way. First, consider than ice skates have asymmetric glide. That is, an ice skate that is gliding down the ice straight ahead will glide very well, an ice skate that is deflected sideways a bit will try to turn (or, if done suddenly, skid), and a horizontal ice skate will cause a shower of snow:

Edge jumps exploit this brilliantly: just before the takeoff, the skater applies a rotational force to his skate. The skate could theoretically continue to travel in a straight line while skidding (and skates will unless they are regularly sharpened), or, since friction would resist that, it will change its path to a circular one. Now, all the skater has to do is apply their jumping energy to the outside of this new circular path, perpendicular to the direction of motion. The coefficent of friction between the blade and ice at this angle is so strong that it can be a suitably secure "platform" to jump off of.

But the skater can only use one foot! Where does the rest of the jumping power come from?

The solution to this problem is difficult to preform on the ice, but quite easy to explain physically. Take for example this image sequence of a double axel takeoff:

(Photo Subject Mirai Nagasu, source: iCoachSkating)

As you can see, the skater thrusts her leg up at the same time she pushes off the ice with the other foot. Since each human leg averages about 17.3% of that person's body weight, this change in upward momentum is a huge help in increasing jump height.