The History of

Planet Finding

Since the 1940s, it has been commonly accepted that planets should be

relatively common in space. Unfortunately,

the limits of science has made it almost impossible to find them until

quite recently. The only planets discovered by

scientists before the 1990s were, of course, Uranus and Neptune (for

ease of reading, we will ignore Pluto as it is

no longer considered a planet). While they are not extrasolar planets

by any means, the discovery of each is

important in understanding how our present-day search began.

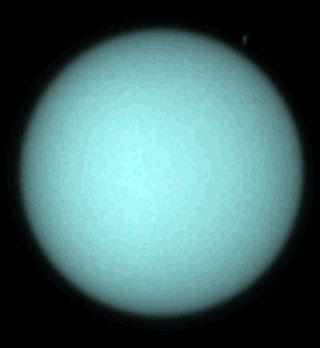

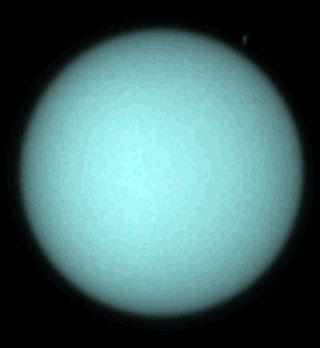

Uranus was discovered by William Herschel, an amateur astronomer but

professional musician. Herschel did not set

out to find a planet, but instead merely noticed its movements across

the zodiac during his research. Charles

Messier, a French expert, determined it was not a comet, and William

became famous for first noticing the planet,

though amusingly it was soon determined that Uranus had been observed

infrequently since 1690.

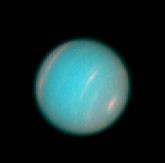

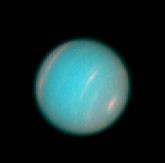

Continued observations of Uranus began to frustrate astronomers, as all

attempts to predict its orbit failed. No path

predicted would be followed for extended periods of time. In the 1830s,

astronomers began to suspect that another

planet was influencing the orbit of Jupiter. In the mid '40s,

mathematics were completed and Neptune was found

through no other means than following the path of its gravity. This

would lay the foundation for the discovery of

extrasolar planets.

In 1990, the first extrasolar planets were discovered orbiting a

pulsar. Because of the peculiarities of a pulsar, each

sends a beam of radio energy to us on a set cycle, at a perfect rate.

This one had irregularities, and it was realized

that just as Uranus' orbit was affected by the gravity of a planet, so

was the spin of pulsar PSR 1257+12. Once

planets were proved possible, the search began, and starting in 1995,

planets were found at an ever-increasing rate.