Finding Extrasolar

Planets

There are many methods of detecting extrasolar planets currently

available.

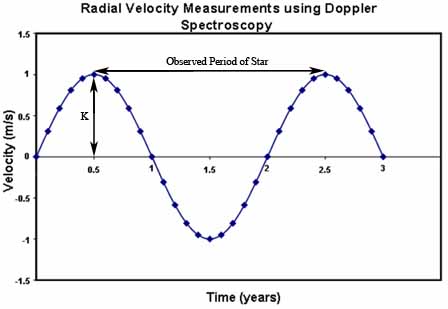

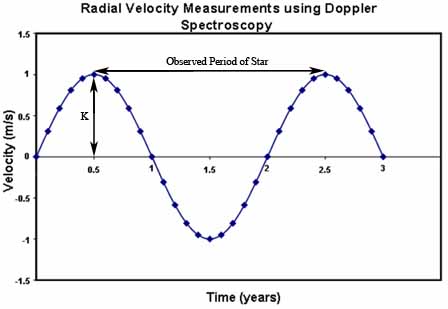

The most successful method is doppler spectroscopy. The laws of gravity

make it clear that all masses pull on all

other masses at a rate inversely proportional to their distance.

Because of this, all planets affect the motion of their

stars, with the most massive ones pulling the most strongly. This can

be observed simply with telescopes focused

on any given star, looking for it to move back and forth slightly over

a period of time.

This method has two flaws. Firstly, the most easily detectable planets

are, unfortunately, either very massive or

very close to their star (or both). Because humanity lives on a small

planet at a safe distance from our sun, these

planets are only curiosities. Second, a class of object between planet and star exists, and

these are also invisible

except for gravity. Though these masses (called brown dwarves) are also

scientifically interesting, they are not the

planets we're looking for.

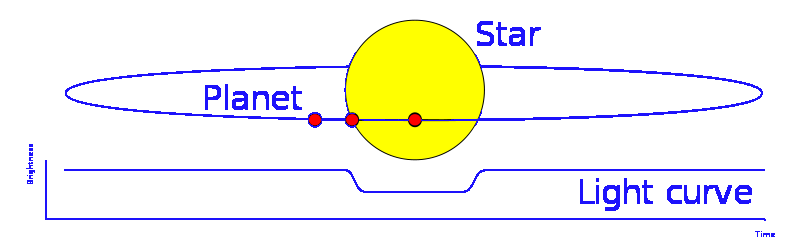

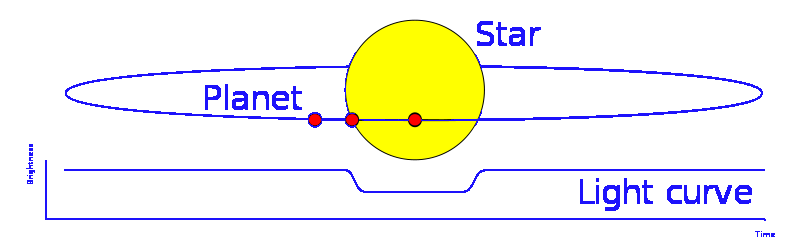

The next most popular method is the transit method. If a planet passes

between us and the star, the apparent

luminosity of the star will decrease. This method has many flaws,

however. The major problem is that many planets

will not pass between us and their star. Another is that other things

can cause the apparent decrease in brightness.

While the transit method has detected planets, doppler spectroscopy has

often been used to verify said planets.

Finally, detecting protoplanetary discs can be of great help. This of

course only works with young star systems,

and we are still dependent upon the angle, but if one is found, the

light of the star at the center can be blocked out

and the tracks that possible planets move through can be detected. The

image on the main page of this website

shows just such a disc. Other forms of direct detection have been used,

but this is a very inefficient method.

Theoretical methods have also been proposed, but none have been

successful at this time.