Glacier Movement

A glacier must be capable of movement to be called a glacier. The velocity of glacial ice involves many factors, including the temperature and thickness of the ice, the amount of slope to the valley, and the friction of the valley walls and floor.

Types of movement

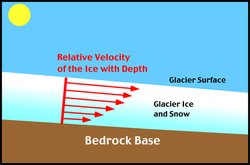

One form of movement is from the plastic deformation of the ice. This is the tendency of ice to start flowing downslope under the stress of its own weight when a certain thickness is achieved. When the glacial ice is subjected to a high enough magnitude of stress due to its thickness, along with the downslope component of the weight, the ice will start to flow. The upper and central parts of a glacier flow more quickly than the bottom portions, where the friction of the valley walls and floor restrict it's velocity from increasing.

Relative speed of glacial ice movement

http://www.eoearth.org/article/Glacier?topic=54335

Basal sliding is another type of glacial movement. Due to the low thermal conductivity of ice, thicker glaciers trap heat flowing upward toward the surface. If there is enough heat, the ice at the base of the glacier will begin to melt. Also, the large amount of pressure from the weight of the ice will lower its melting point, causing the ice making contact with the ground to melt. This melting forms a layer a water which results in less friction between the glacier and the ground, facilitating greater movement of the glacier.

Crevasses

The pressure is lower near the surface of a glacier making the ice more brittle, where crevasses are likely to form. These cracks form due to velocity differences in the glacial movement. As a glacier moves in different directions and with different speeds, it causes shear stress on the ice to where two sections will break apart. Transverse crevasses form transverse to the glacial flow as it accelerates on a steeper slope. Longitudinal crevasses form partially parallel to the flow where there is lateral expansion of the glacier. Crevasses will also form around the edges of a glacier from the reduction of speed caused by friction on the valley walls.