In ancient times, lightning was

seen as a tool of the gods.† In Viking

legend, it was Thorís hammer striking an anvil in the sky that was responsible

for lightning.† For the Greeks, it was

Zeus who threw lightning down to the earth.†

North American Indian tribes thought that lightning was produced by a

mystical bird with flashing feathers whose flapping caused thunder.

Even now,

hundreds of years after the first scientific work with lightning, people remain

in awe of its power.† In the 18th

century, the first systematic scientific study of lightning was carried out by

Benjamin Franklin.† Before Franklinís

experiments, electrical science had grown to the point of separating positive

and negative charges, and had developed primitive capacitors.† The sparks produced in laboratories were

noted as similar to lightning, but it was Franklin who designed an experiment

to prove that lightning was electrical. †

Benjamin

Franklin believed that clouds must be electrically charged, which would mean

that lightning must also be electrical.†

For his first experiment, he stood on an electrical stand with an iron

rod in one hand to achieve an electrical discharge between the other hand and

the ground.† If Franklinís belief that

the clouds were electrically charged was correct, then sparks should leap

between the iron rod and a grounded wire held by and insulating wax candle.† This test method was published in London and

performed in both England and France.†

Thomas Francois DíAlibard of France was the first to successfully

perform this experiment in May of 1752, when sparks were seen jumping from the

iron rod during a thunderstorm.

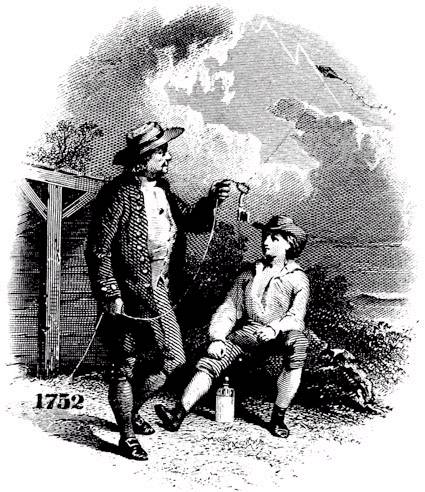

Image taken

from: http://www.thebakken.org/electricity/Franklin-kite-experiment.html

Before Benjamin

Franklin achieved results from his first experiment, he devised a better way of

testing his hypothesis.† This new

experiment was his infamous kite experiment.†

The kite replaced the iron rod, as it could reach a higher

elevation.† In 1752 Franklin found

success during a Pennsylvania thunderstorm.†

When a storm cloud passed over his kite, sparks flew from a key tied to

the bottom of the damp kite string.† He

was also able to collect a charge on a Leyden Jar, which was a simple

capacitor, that was connected to the key via a thin metal wire.† Using this he was able to determine that the

charge was negative.† Franklin was not

affected by the charges thanks to an insulating dry silk ribbon that connected

the kite string to Franklinís hand.†

Upon reaching out to touch the key, the negative charges were attracted

so strongly to the positive charges in his body that a spark jumped to

Franklinís hand.†† Many who have

attempted to duplicate Franklinís experiment have died trying.