Early Years

January 8th, 1942 was the 300th anniversary of the death of Galileo Galilei. It is fitting that this would also be the day that Stephen Hawking was born, as if to foreshadow the work of the work of this newborn. Stephen Hawking, while not always the stellar student expected of a genius, has contributed greatly to cosmology with his discovery of gravitational singularities, the mechanics of black holes, and attempting to explain them to the layman.

During WW2 England had negotiated with Germany that in exchange for not bombing the university cities of Heidelberg and Gottingen, Germany in return would not bomb England’s two most renowned campuses Oxford and Cambridge. It was this reason why Frank and Isobel Hawking left London to the relative safety of Oxford where their son Stephen Hawking was born in 1942. Growing up Stephen’s teachers recognized him for a very sharp child but his grades never quite reflected his true genius. At 17, Stephen took the entrance exam for Oxford University. While this attempt was intended just for practice, his scores were such that Oxford offered him a scholarship on the spot which he accepted. Stephen had some arguments with his father about what he should pursue academically. His father who was a doctor wished for his son to follow in his footsteps, and to study biology while an undergrad leading into med school. Stephen was infatuated with mathematics though, and thought biology contained too much description and wasn’t discrete enough. The two ended up compromising on physics, as his father was adamant that he wouldn’t be employable except as a professor with a degree in mathematics.

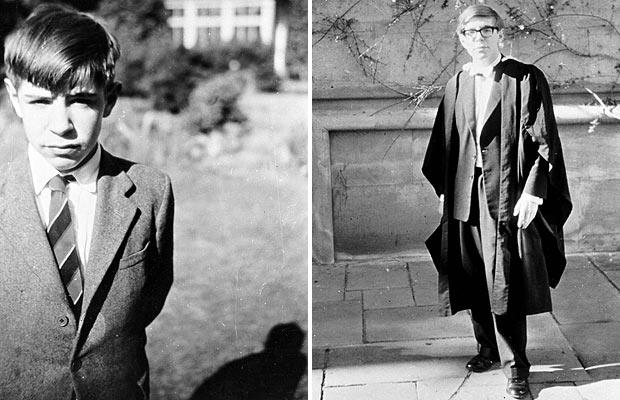

Stephen before the onset of ALS

Stephen was largely depressed his first year at Oxford. He felt ostracized from his peers as the average student entering at the time was 19, or even a few years older after having served for the military. He was still too young even to go to the pub. This led to a large amount of time spent in his room reading while drinking beer. Stephen eventually found himself though and became quite social- his sharp wit and tongue serving him well at parties. He even joined the rowing team, but as coxswain of the boat. His smaller frame suited better sitting aft steering and calling cadence than that of a rower. His habits as a student were still not exemplary either- spending only about an hour a day on studies. This is something he would later regret as it instilled bad study habits and hindered him in his graduate work.

Towards the end of his time as an undergrad he applied to study at Cambridge for cosmology. Stephen also got an offer from Fred Hoyle, renowned physicist and astronomer, that if he got a first-class honors degree that he could study under him for his graduate work. Stephen ended up botching a few of his exams though, scoring between first and second class. As was usual for these cases he was called in front of a review board to decide his fate. Stephen was very confident if not a little full of himself at the interview, and when asked what his future plans were he replied, “If I get a first I shall go to Cambridge. If I receive a second I shall remain at Oxford. So I expect that you will give me a first.”[1] Dr. Berman is quoted as later saying, “They were intelligent enough to realize they were talking to someone far cleverer than most of themselves.”[2] Stephen Hawking was accepted into Cambridge fall of 1962, although Hoyle reneged on his offer, something that Stephen would not forget. It was now that Stephen regretted not applying himself earlier in his scholastic career, his lack of experience with mathematics clearly showing. While the people who knew him recognized his brilliance, Stephen had not yet made so much as a dent in the scientific community. Even on campus the cosmology department was considered insignificant, overshadowed by other greats such as Watson and Crick had just won the Nobel Prize for discovering the structure of DNA the same year.

The iconic image of Stephen Hawking known round the world, the man with a disabled body trapped in a wheel chair, his mind working with perfect clarity- a physical incarnation of brains versus brawn was not always so. It was around the time that he entered Cambridge at the urging of his parents to visit a doctor about bouts of clumsiness he was having. Stephen was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig's disease, which causes deterioration of the brain and spinal cord. Its progression eventually leaves the patient without use of limbs, the ability to speak, and eventually incapable of breathing or swallowing leading to death. The doctors estimated that he only had a few years to live. After wallowing in self-pity, Wagner records, and vodka for the few months Stephen emerged with renewed vigor, this time to make a name for himself. Helping him out of his depression was Jane Wilde, who would later become his wife of over twenty years.

Our knowledge of the universe at this time was (and still is) limited. It was only 50 years earlier that Einstein had presented his theory of relativity, Karl Schwarzschild had only postulated about the existence of black holes (a term not even coined yet), Hubble’s observations of an expanding universe were still debated in scientific communities and had been openly refuted even by Einstein- who had theorized about a static universe. Hoyle himself had dismissively referred to the idea of an expanding universe as the ‘big bang’, a name that would later stick, sarcastically likening it to “…a party girl jumping out of a cake.”[3] One of Stephen’s first steps towards recognition came in 1964 where Hoyle was the keynote speaker at a dinner for the Royal Society in London. Hoyle was presenting about the static universe, on unfinished work he thought would discredit Hubble. Before the speech Stephen had obtained the notes though, and finished the math. When Hoyle opened to the crowd for questions, Stephen stood and said, “The quantity you are talking about diverges.”[4] Hoyle was irate that he had been ridiculed and humiliated in front of such a crowd. Regardless of Hoyle’s emotions though, Stephen Hawking had just established himself on the stage of cosmology.