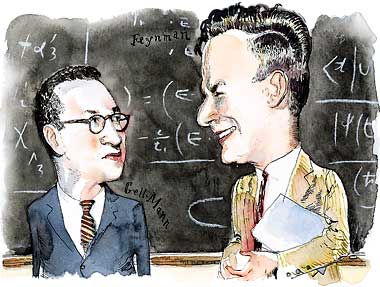

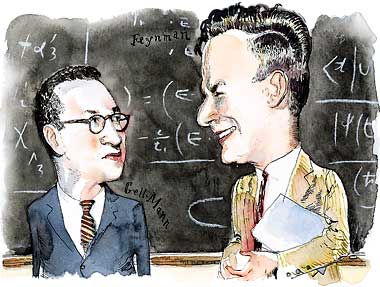

The Jaguar and the fox.

Hard as he tried, Murray Gell-Mann could never make himself into a legend like his rakish colleague and collaborator, Richard Feynman -- even if he was probably the greater physicist

by George Johnson

ALONG the far wall of the spacious, newly renovated bookstore at the California

Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, stands a shrine to Richard Feynman, the

university's celebrity scientist. Reaching from floor to ceiling, shelf upon

shelf is loaded with multiple copies of more than fifty Feynman hits -- books,

CDs, cassettes, and videotapes capturing the outpouring of words written about

or uttered by the man many consider to be the greatest physicist of the second

half of the twentieth century.

Feynman fans can choose among three biographies, two collections of dictated

autobiographical reminiscences, dozens of lectures, a collection of the scientist's

drawings (he also liked to scrawl on placemats at a topless bar), and Safecracker

Suite, a recording of Feynman slapping the skins of bongo drums and regaling

listeners with his capers as a young physicist on the Manhattan Project. A precursor

to today's computer hackers, Feynman picked the locks on the vaults containing

atomic secrets, and then left taunting notes to show how easily security had

been thwarted.

Since his death, from cancer, in 1988, the Feynman industry shows no sign of

diminishing. Recent books and recordings, including Six Easy Pieces, Six Not-So-Easy

Pieces, and Feynman's Lost Lecture, all sold well, and now a new collection,

The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, has made science best-seller lists. The

Mark Taper Forum, in Los Angeles, is planning a production next year called

Tuva or Bust!, with Alan Alda as Feynman.

Many physicists are puzzled and a little annoyed to see their old colleague, brilliant as he was, elevated to the level of Einstein. But no one finds the hype more annoying than Murray Gell-Mann. Those who paid attention in physics-for-poets classes may remember Gell-Mann as the man who, working down the hall from Feynman, discovered quarks -- the tiny subparticles from which just about everything is made. (He famously took the spelling from a line in James Joyce's Finnegans Wake: "Three quarks for Muster Mark!") It was Gell-Mann who came up with the Eightfold Way -- an elegant organizing scheme that made sense of the "subatomic zoo," herding some 100 unruly particles into their proper cages. For years a favorite argument among physicists was over "Who is smarter, Murray or Dick?"

But Gell-Mann -- who, in semi-retirement, continues to lecture and write -- has, to his bewilderment and consternation, never become as famous as his old sparring partner. At the Caltech bookstore one is lucky to find a single copy of his book, The Quark and the Jaguar, which did not sell nearly as well as "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!," a collection of humorous anecdotes that Gell-Mann snidely calls "Dick's joke book." When Physics World recently asked scientists to name the greatest physicists who ever lived, Feynman came in seventh, just behind Galileo. Gell-Mann didn't make the top ten -- or even get a single vote. When he showed up at President Clinton's millennium New Year's Eve ball squiring the actress Talia Shire (famous for playing Rocky Balboa's wife), the cameras barely blinked.

The intimidatingly smart top players in particle physics compete on a level playing field. The field is also rather constricted, with only a few big ideas being batted around at any one time. Most prizewinning discoveries are made by two or more thinkers simultaneously. What makes one a superstar and relegates another to obscurity often depends less on the work itself than on political acumen.

Gell-Mann, as competitive and as savvy as they come, has easily grabbed top honors, including the Nobel Prize for Physics. But there are other factors that count in the manufacture of fame. Gell-Mann knew how to package ideas, and he had a knack for giving whimsical, and unforgettable, names to the most abstract concepts in science. Feynman had a more vital gift: he knew how to package himself.

WHENEVER a new particle is discovered now, science fans expect it to have a

funny name. Up quarks, down quarks, strange quarks, charmed quarks, top quarks,

bottom quarks -- in addition to these six "flavors," quarks come in

three "colors": red, green, and blue. There is no end to the inventiveness

that has become part of the subculture of particle physics. Bottom quarks and

anti-bottom quarks (stuck together by -- what else? -- gluons) can be combined

to form an exotic compound called bottomonium. It is easy to forget sometimes

that all this jabberwocky refers to real things.

No one deserves more credit, or blame, for all this verbal whimsy than Murray

Gell-Mann. A prodigy who graduated from high school at age fourteen (his classmates

thought of him as a walking encyclopedia), he had earned a Ph.D. in physics

from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by the time he was twenty-one.

He was brought by Robert Oppenheimer to the Institute for Advanced Study, in

Princeton. From there, in 1952, he went to work with Enrico Fermi at the University

of Chicago. It was in the sweltering heat of a Hyde Park summer that Gell-Mann

put together the pieces of his first great hit: a theory of strange cosmic rays

that seemed to defy the laws of physics.

By all rights these beams of particles, raining down from space, should have

decayed as soon as they were snared by the physicists' detectors. But they lingered

maddeningly longer -- a full hundred-millionth of a second. When Gell-Mann figured

out the physical quality that endowed these interlopers with their unexpected

longevity, he decided to call it "strangeness." These were, after

all, strange particles. A rival theorist, Abraham Pais, urged his colleagues

not to adopt this undignified name, but "strangeness" stuck. And a

good thing for Gell-Mann that it did: a Japanese physicist, Kazuhiko Nishijima,

made the same discovery at about the same time; he called it the "eta-charge."

One is not likely to remember Nishijima from the physics-for-poets class.

Other particles that the new theory said should exist (one, with a strangeness of 2, was, Gell-Mann said, "doubly strange") were soon found by experimenters. Gell-Mann was suddenly a star. Refusing an offer from the University of Chicago to double his salary, he accepted his first tenured position, at Caltech. It was not the southern-California lifestyle that lured him (he found the place only slightly less depressing than Chicago) but the presence of the physicist he most wanted to work with: Richard Feynman.

In a field that Gell-Mann thought suffered from intellectual phoniness, Feynman, with his madcap energy, seemed to have real genius. He had made his name in 1948, when he and two other scientists, Julian Schwinger and Sin-itiro Tomonaga, figured out how to fix a flaw in the theory of quantum electrodynamics, which explains light, magnetism, and electricity. Like a buggy piece of software, QED, as it is called, kept coughing up answers that were ridiculous (saying, for example, that a particle's mass or charge was infinite). Each of the three theorists solved the problem in a different way, but it was Feynman's vivid approach, calculating with ingenious little pictures soon to be called Feynman diagrams, that made the strongest impression. Feynman dismissed his own accomplishment (which would earn him and the others a Nobel Prize) as so much mathematical hocus-pocus. But Gell-Mann thought that Feynman, more than most others, had a way of seeing beyond the dazzling surface of the equations to what nature was really doing.

After Gell-Mann and his wife arrived in Pasadena, in the spring of 1955, Dick and Murray, as everyone soon called them, became inseparable. Strolling Caltech's immaculately landscaped campus or dueling at the chalkboard over some calculations, the two scientists discussed physics for hours -- "twisting the tail of the cosmos," as Gell-Mann later put it. But when it came to almost anything but physics, their personalities clashed.

Gell-Mann, who had been raised in a poor family of Jewish immigrants in Manhattan, was determined to become a debonair man about town. He dressed impeccably, lecturing in well-tailored sport coats and ties on even the hottest summer days. He knew just which wines and dishes to order at a restaurant, and paid with his Carte Blanche. Still the overeager schoolboy, he pronounced foreign words perfectly and corrected new acquaintances on the pronunciation of their own names.

And then there was Feynman, tieless, in shirtsleeves, grabbing lunch at a greasy spoon. He had grown up in Far Rockaway, on the outskirts of Queens. Like Gell-Mann, he had never gotten over a need to prove he was the smartest kid on the block. Feynman affected the role of an outsider, a heckler on the sidelines who was ready to deflate anyone who put on airs. Gell-Mann would make a knowing reference to some foreign locale -- pronouncing "Montreal" so that it caught in his throat with an authentic Quebecois growl, or "Beijing" so that it rang like a temple bell -- and Feynman would pretend not to understand him. "Where?" he'd bark back, sounding more like a Brooklyn cabdriver than someone with a Ph.D. from Princeton. The image was as carefully crafted as Gell-Mann's, but few caught on.

THE real trouble started as early as 1957, when Gell-Mann returned from a wilderness trek in northern California to find Feynman strutting around the department proclaiming an epiphany: in a moment of intense clarity he had seen the very secret of what is known as the weak nuclear force, the engine of radioactive decay. Gell-Mann was dumbfounded. He had been mulling over the problem for weeks, and had come to a similar conclusion. But, typically, he hadn't written the idea up.

Ever since he was in college, Gell-Mann had suffered from a debilitating case of writer's block. He had failed to complete his senior thesis at Yale and had struggled over his Ph.D. dissertation on nuclear theory, preferring to hole up in the library reading the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Now fearful of being scooped, he rushed to beat Feynman into print. Finally the department chairman intervened, persuading his two stars that it would look silly to have competing papers come from the same campus. They agreed to collaborate.

When the theory made its debut, in January of 1958, it lacked the Gell-Mann touch: bereft of a clever name, it was dully called the V-minus-A model. But the power of the idea showed through. Always looking for the scientist who would become heir apparent to "the mantle of Einstein," the news media seized on the two geniuses from Caltech. Newsweek declared that the "dapper, cocky" Gell-Mann was many physicists' choice for "brightest light in his esoteric field." With a "Madison Avenue fastidiousness about his clothes" and his "boyish face and quick tongue," the magazine observed, Gell-Mann exhibited "a kind of sharp intellectual fussiness that has more than once wounded his colleagues." Time weighed in with a portrait of Feynman as a bongo-playing beatnik of uncanny mathematical powers who liked to pick locks in his spare time. Explaining a recent decision to become a teetotaler, Feynman said, "I got potted in a Buffalo bar one night and wound up with a lulu of a black eye."

Unaware of how forced the partnership had been, some physicists thought they saw the beginning of a powerful intellectual alliance, with the world's two smartest physicists taking on science's remaining mysteries. Gell-Mann seemed to have the same hope. Though Feynman was essentially a loner, Gell-Mann loved the camaraderie of collaboration. And he was terrified of heading solo into the void with an idea that might turn out to be wrong. He and Feynman had been trying to understand a problem involving neutrinos, the evanescent particles that fly through planets almost as easily as through empty space. The puzzle could be explained, they surmised, if there were actually two kinds of neutrinos (they called them red and blue). Gell-Mann wanted to write up the idea, but when Feynman resisted, he didn't have the nerve to go it alone. The theory, with others' names on it, later turned out to be correct, and Gell-Mann added Feynman's obstinacy to his lengthening list of grievances.

GELL-MANN spent 1959 working in Paris, polishing his French and indulging a growing taste for haute cuisine. After long, wine-soaked lunches with his French colleagues he would return, a little bleary, to his office at the Collège de France and ponder his next big problem: How were the dozens of different particles that kept popping up in accelerator experiments related? Appearing in many shapes and sizes, they appeared to have been created almost at random -- an affront to the search for order.

In December of 1960, after a chance conversation with a Caltech mathematician, Gell-Mann saw how to make the particles fit together beautifully in groups of eight. The Israeli physicist Yuval Ne'eman came up with the same idea at the same time, calling it by its mathematical name, SU(3). Gell-Mann, as usual, picked the name that endured: because he had been reading about Buddhism, he decided to call his classification scheme the Eightfold Way, a mocking reference to the Buddha's eight-step plan for righteous living. Ne'eman later said that one of the crucial things he learned from Gell-Mann was the importance of packaging a theory.

Gell-Mann's accomplishment -- among the most spectacular to emerge in the second half of the century -- is often compared to Dmitri Mendeleev's Periodic Table of the Elements, in which the hundred or so different atoms line up to form columns of substances with common properties: the noble gases, the rare earth metals, and so forth. The source of the order wasn't understood until scientists discovered that atoms, whose name means "indivisible," actually had minute parts. Elements that behaved in a similar manner had the same number of electrons in their outermost shells, the chemical faces they showed to the world.

Gell-Mann's crowning achievement was to see that the order of the Eightfold

Way could be explained if subatomic particles also had structure. Instead of

being a featureless glob of positive charge, as had been widely assumed, a proton

was made of three tiny particles called quarks. Neutrally charged neutrons were

made of a different combination. (Again Gell-Mann wasn't the only one to come

to this realization. A young physicist named George Zweig devised a practically

identical theory almost simultaneously, calling the units "aces.")

Feynman didn't find the idea particularly appealing. He all but ignored quarks

until the late 1960s, when experimenters, firing electron bullets at protons,

struck what appeared to be hard little objects inside. His interest finally

piqued, Feynman immediately went to work analyzing the experiment, infuriating

Gell-Mann by refusing to call the subparticles quarks. He insisted on his own

name, "partons." Gell-Mann couldn't believe Feynman's temerity. A

mongrel of Latin and Greek, "parton" was to his ear extremely ugly.

Gell-Mann started calling them "put-ons," and grumbled that Feynman

was trying to hijack his theory.

BY the mid-1980s what had begun as a friendly rivalry was a bitter feud. Gell-Mann

had become notorious for his bad temper. Among his cronies, the nasty names

he coined for rivals were as familiar as the catchy terminology he applied to

particles. Leon Lederman was "the plumber," because he was an experimenter

rather than a theorist. The distinguished theorists C. N. Yang and T. D. Lee

were "those two Chinamen from New York."

Gell-Mann respected Feynman too much to saddle him with an insulting name. But Feynman was driving him crazy. Though hardly a prude, Gell-Mann would bristle as Feynman ebulliently described his latest escapades at the Esalen Institute, the New Age spa at Big Sur. Feynman would mock the fuzzy-headed philosophy of the place as he soaked in a hot tub and flirted with naked sunbathers.

The breaking point came in 1985, when Feynman and Ralph Leighton, the son of a Caltech physicist, compiled some of Feynman's tales into "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!": Adventures of a Curious Character, which became a surprise best seller. In story after story Feynman came off as the holy fool seeing through everyone else's pretenses. Flipping through the pages, Gell-Mann found Feynman's account of the theory of the weak nuclear force, the one they had reluctantly collaborated on. "I was very excited," Feynman said. "It was the first time, and the only time, in my career that I knew a law of nature that nobody else knew." Gell-Mann, enraged, said he would sue. In a later edition Feynman conceded that Gell-Mann and two other physicists had also thought of the idea. But the disclaimer didn't heal the wound.

For all his accomplishments, Gell-Mann couldn't be happy until he had written a best seller like Feynman's. Adding to his melancholy, "Surely, You're Joking" was followed in 1988 by Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time, which sold more than nine million copies. To Gell-Mann's colleagues, a book of light-hearted anecdotes told by their intense and pedantic friend seemed a dubious prospect. It would have to be called, one of them said, "Dammit, Murray, You're Right Again!" Others remarked that Gell-Mann, unlike Hawking, didn't have the advantage of being confined to a wheelchair.

"I'm writing a book for peasants," Gell-Mann would say dismissively. As it turned out, he wasn't up to the task. The Quark and the Jaguar became legendary in publishing circles for the size of the advances it attracted -- reported to be more than a million dollars worldwide -- and for the toll in human suffering it took on friends, colleagues, ghostwriters, editors, and, finally, readers. It was the Heaven's Gate of science books.

Submitted late and incomplete, the manuscript, composed one agonizing sentence at a time, was rejected by Bantam Books. Shortly afterward Gell-Mann had a mild heart attack. When the book was finally resold, for substantially less money, it did well, but on a far smaller scale than Feynman's. Gell-Mann just couldn't match Feynman as a storyteller. And although Feynman didn't actually write his own books, many of his lectures, transcribed for the popular-science market, were gems of clarity and color. Feynman thought in pictures, Gell-Mann in abstractions. When Gell-Mann tried to convey his ideas to the public, the explanations often fell flat. Making up funny names for particles, it turned out, wasn't enough.

IN the end, Gell-Mann may turn out to be the more important physicist. The Eightfold Way and quarks now lie at the foundation of the Standard Model -- the theory that explains how matter is made. It is hard to imagine a more far-reaching contribution to understanding the physical world. Trying to pin down Feynman's significance is much harder. He himself considered his Nobel Prize-winning work more of a virtuoso technical performance than a meaningful insight into nature, and it was completed when he was thirty. After that he made scattered contributions -- a theory of a phenomenon called superfluidity, for example. His greatest legacy may be Feynman diagrams, the little pictures that vividly describe particle interactions. (Gell-Mann would deny him even that distinction, obstinately calling them "Stückelberg diagrams," after an obscure Swiss physicist who devised a similar notion.)

Neither Feynman nor Gell-Mann got what he most wanted. Feynman never stopped lamenting that he had missed the thrill of being the first to understand a new truth. Gell-Mann has never become a household name. And the friction between them prevented the kind of alliance that might have led to even greater discoveries -- great enough, perhaps, to satisfy both these impossible men.